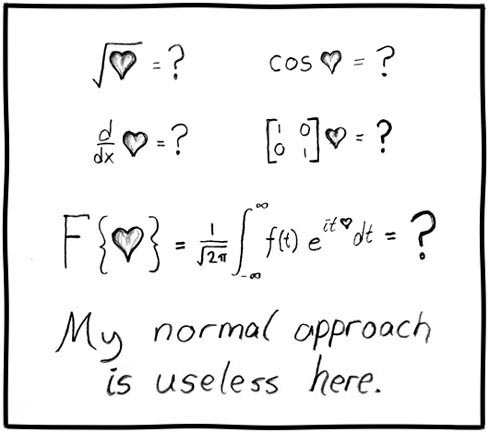

Useless is one of my favorite xkcd installments:

Useless (xkcd), by Randall Munroe – some rights reserved

This is obviously an useless approach, but it’s hard for a math undergrad to see so many question marks! The second equation, in particular, got me thinking for quite a while:

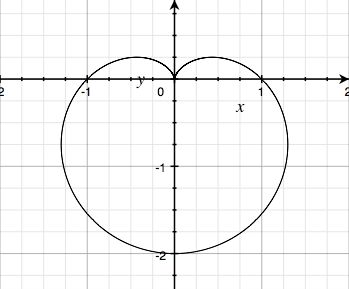

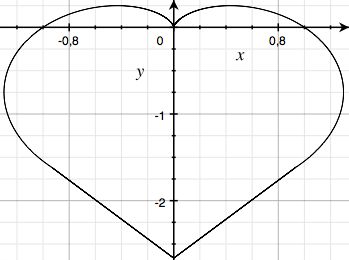

How could someone extract the cosine of a heart? It seems impossible – unless you can represent a heart in mathematics. And I remembered a very interesting curve from calculus that might be a candidate for that: the cardioid. Its name implies some relationship with a heart shape. I was never much sold on that, but you can judge by yourself:

It may not be the best heart representation ever seen, but at least it is described by a very simple formula – if you don’t mind using polar coordinates:

If you change the signal from minus to plus and/or the function from sin to cos you can change the orientation of the graph. As it is, it may fit our plans, except for two problems:

- The top does indeed look like the upper part of a heart symbol, but the bottom is a bit frustrating in that sense;

- You still can’t calculate the cosine of a polar curve (at least, not in a graphically meaningful way).

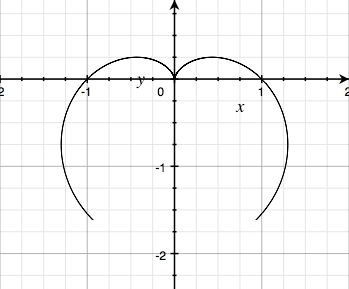

We can tackle the first problem by replacing the bottom of the curve. First we draw just the part that fits our heart’s desire for a heart, that is, the one with θ ∈ *[-(1/3)π, (4/3)π*]:

Now we can add a second curve that fits the remaining part with the more traditional sharp edge. But first let’s convert the formula to its cartesian equivalent, using the definitions: x(θ) = ρ.cos(θ) and y(θ) = ρ.sin(θ). Then we have, for θ ∈ *[-(1/3)π, (4/3)π*]:

y(θ) = sin(θ)-sin2(θ)

Making a “tip” on the bottom requires x to vary on the range between the two loose edges on the graph, and y is just a straight line going down then up – the modulus function will help us. But doing so using the same θ parameter on the complimentary range (from (4/3)π to -(1/3)π) requires a few substitutions and manipulations to put everyting in place. It gets like this:

y(θ) = 2|(θ-(9/6)π)|+sin(4π/3)-sin2(4π/3)-π/3

Yes, it can be simplified, but I’m too lazy focused on the main problem now. The resulting graph is:

which fits nicely into the top part:

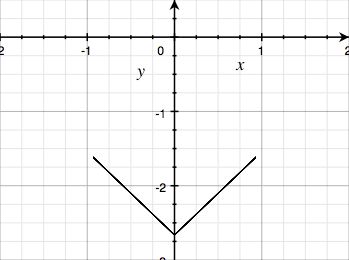

The conversion to cartesian formulas also solves the other problem: it is reasonable to think that the cosine of a system of equations is obtainable by applying the cosine function to each of the equations – you can think about that either as applying the cosine to each coordinate of each point, or as doing that to the equations in matrix form. Or you can just use your heart and believe when I say it’s reasonable. Your call.

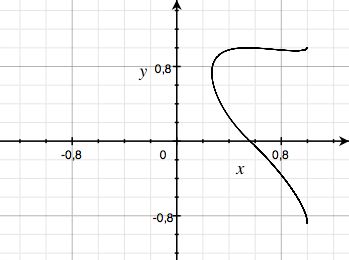

Anyway, by applying the cosine to the formulas above, we obtain the following graphic, which represents cos(♥):

The most frustrating part is that it’s not a closed curve – one might imagine a line linking the two edges and try some rorschach-esque interpretation (a friend of mine suggested a sillhuete of a female bust, but his heart was under heavy stress at the moment). Another interpretation is to realize that you simply end up with a broken, deformed heart (which is what happens after you find out that math is all you have left to deal with issues in your life).

Epilogue: The same techinque could be applied to the other formulas, which is, as usual, left as an exercise to the reader. A few pointers:

- The identity transformation looks trivial, but that is not acceptable (check the tooltip on the comic);

- Formulas that already treat the heart as a function (such as d/dx) can possibly be applied in a more straightforward way;

- Munroe seems to have replaced the Fourier transformation with a Laplacian on the comic’s t-shirt. Heck, work is never over!

Comments

mOa

Sim. Não há mais dúvida: Hail King of All Nerds!!!!

chester

Just for the sake of completeness, I've found this slightly curvier (and simpler) heart function: http://bit.ly/nJZFjI