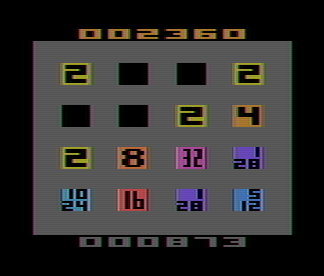

As everyone else on the planet, I got hooked on 2048 and amazed by the variants that sprouted. Its simple rules and graphics are one distinctive characteristic. “It’s so simple”, I thought, “that it really could have been done on an Atari”. And once you have such an idea…

That’s right: this is a version of 2048 for the Atari 2600! It took me about 16 hours of work to get to a playable prototype, and about 50 hours for the final version, spread over a couple weekends and nights during which I was refining the core game and squeezing features like sound, two-player mode, and a high score.

During this period it briefly made the front page of Hacker News, received lots of great feedback on Atari Age and RVG, and got a couple of contributions (bug fix, PAL support). The 2048 source was also helpful - even though I had to rethink the whole shifting/merging strategy, it provided a nice foundation with very readable code.

The project page has all the instructions and files you need to run it on an emulator, on a real console or even in your browser. The remainder of this post shows some technical notes (which can also be found at the main assembly source file).

Cell Tables

The game stores each player’s tiles in a “cell table”, which can contain one of these values:

- 0 = empty cell

- 1 = “2” tile

- 2 = “4” tile

- 3 = “8” tile

- 4 = “16” tile

…

- n = “2ⁿ” tile (or, if you prefer: log₂k = “k” tile)

…

- 11 = “2048” tile

- 12 = “4096” tile

- 13 = “8192” tile

(I could have followed, but try drawing 5 digits on an 8x10 tile :-P )

- 128 ($7F) = sentinel tile (see below)

In theory, we’d use 16 positions in memory for a 4x4 grid. Navigating left/right on the grid would mean subtracting/adding one position, and moving up/down would be done by asubtracting 4 positions (that is, “cell table y offset” would be 4)

However, such an arrangement demands some complicated (for 6507 standards) boundary checking, so instead I surrounded the grid with “sentinel” or “wall” tiles. That would need 20 extra cells (bytes) to store the grid:

first cell -> SSSSSS S = sentinel, . = data (a tile or empty cell)

7th cell -> S....S

13rd cell -> S....S

19th cell -> S....S

25th cell -> S....S

SSSSSS <- last (36th) cell

Some space can be reclaimed by removing th left-side sentinels, since the memory position before those will be a sentinel anyway (the previous line’s right-side sentinel).

We can also cut the first and last sentinel (no movement can reach those), ending with with this layout in memory (notice how you still hit a sentinel if you try to leave the board in any direction):

first cell -> SSSSS S = sentinel, . = data (a tile or empty cell)

6th cell -> ....S

11th cell -> ....S

16th cell -> ....S

21st cell -> ....S

SSSS <- last (29th) cell

For manipulation, the only change from the trivial 4x4 is that the cell table vertical y offset is now 5 (we add/subtract 5 to go down/up). The first data cell is still the first cell plus the vertical y offset.

Grid Drawing

The grid itself will be drawn using the TIA playfield, and the tiles with player graphics. The Atari only allows two of those graphics per scanline (although they can be repeated up to 3 times by the hardware), and we have four tiles per row, meaning we have to trick it by changing the graphics as the TV “beam” is drawing the screen (for more details, check this presentation)

To translate the cell table into a visual grid, we have to calculate, for each data cell, where the bitmap for its value (tile or empty space) is stored. We use the scanlines between each row of cells to do this calculation, meaning we need 8 RAM positions (4 cells per row x 2 bytes per address).

We use the full address instead of a memory page offset to take advantage

of the “indirect indexed” 6502 addressing mode, but we load the

graphics table at a “page aligned” location (i.e., a $xx00 address),

so we only need to update the least significant byte on the positions above.

Shifting

The original 2048 uses a “vector” strucutre that points two variables with

the direction in which the tiles will shift (e.g., vector.x = -1, vector.y

= 0 means we’ll move left). It also processes them from the opposite side

(e.g., start from leftmost if it’s a right shift), making the first one

stop before the edge, the second stop before the first, etc.

It also marks each merged tile as so (removing the marks between shifts), so it can block multiple merges (i.e., the row “ 4 4 8 16” does not go straight to “32” with a left, but first becomes “8 8 16”, then “16 16”, then “32”. Similarly, “2 2 2 2” would first become “4 4”, then “8”. Finally, it stores the previous position for each tile, and lets the awesomeness of CSS move them all at once with ease.

2048 2600 translates this idea to the Atari by implementing a “single-byte vector” which can be -1 or +1 for left and right; and -5 or +5 for up and down (remember: each row is 4 bytes plus a sentinel tile). Each tile will be pushed (by adding the vector value) until the next cell is non-empty and does not match its value.

The vector signal also tells us where to start to ensure they all get to the end: negative (left/up) start processing from the first cell and positive (right/down) start from the last.

Merged tiles are marked by setting bit 7 on their values, which will be easy to check in upcoming pushed blocks without needing extra memory. We’ll only miss the animations, but we can’t have everything.

Timings

Since the shift routine can have unpredictable timing (and I wanted some freedom to move routines between overscan and vertical blank), I decided to use RIOT timers instead of the traditional scanline count. It is not the usual route for games (as they tend to squeeze every scanline of processing), but for this project it worked fine.

Comments

David Bock

OMFG! I LOVE YOU! I made exactly this point on twitter the other day... that games like 2048, that could have been done on antique hardware, prove there is still plenty of room for innovation in games that don't involve high resolution graphics, in-app purchases, etc.

~15 years ago I looked at what it took to write Atari games and was impressed by the constraints/timing it took. I'm uber-impressed you did this!

chesterbr

:-) Glad you enjoyed it. I've always flirted with the idea of backporting modern games with simple mechanics. I still want to add a few more 2048 characteristics (like indications for when the tiles match, and - if I manage to make it - different colors for each tile value). Cheers!

Matthieu Bdg

Great article personally I use the site

https://www.game-2048.com