Having a relatively short office closure week for the holidays led my wife and I to look for a sunny break from the Canadian winter, and we noticed a lot of Canadians chose Cuba for that.

Between the proximity (it’s a 3-hour flight from Toronto), the relative affordability and our desire to understand the country beyond the usual left/right political narratives, we decided to give it a try. Here are some highlights of our experience and a few things we wish we knew before going.

Preparation

Accommodations: Typical (that is, US-based) travel agency and homestay websites don’t list accommodations in Cuba. Expedia is a notable exception, so we booked and prepaid our stays through it. You usually have two options: all-inclusive resorts (usually close to a beach, where people stay through their whole vacation) and homestays (for those wanting to see the country and talk to the locals, like us). In any case, the websites ask an odd question about your reason for visiting Cuba (and none of the answers matches “tourism”) - that’s because they are required to do so by the US government, so just pick one of the options and move on.

Money: Visa/MasterCard don’t operate there, so you will use cash for everything. Restaurants, stores and experiences will accept US dollars, so bring those. USD 30 should get three basic meals for a person and USD 10 transports you within the same city, so budgeting at least USD 50/person/day (with prepaid stays) is a good idea. Don’t buy pesos (CUP) - you will get the official rate (1 USD = 120 CUP), whereas purchases will go with 200-250 CUP per USD. Change for your USD will usually be CUP anyway - so bring small bills (5/10/20) and use the pesos from change on small purchases, like a coffee or pastry on a street vendor. Don’t count on converting back to USD or spending at the airport, so spend or donate your pesos before leaving.

Food and medication: Be prepared to focus on local specialities such as the Ropa Vieja (shredded beef). You may find other food, but ingredients and spices will be scarce, so don’t expect sophistication. Bring some snack bars and biscuits if you have dietary needs or are a picky eater, and also any medication, seasoning (e.g.: sweeteners) and toiletries you can imagine yourself needing.

Clothing: Winter was mostly warm (above 21ºC with a single rainy day); summer must be 🔥, so pack accordingly. You may consider donating some of your clothes/shoes once you use them. Speaking of which…

Donations: Blame the embargo, the corruption, both or anything else; it doesn’t matter: fact is that Cuba is suffering severe shortages, and the locals will appreciate any donations you can bring (details below). Think dollar store daily essentials that would be hard to get in an isolated country (toiletries, clothing, reading glasses, pens and pencils, crosswords/coloring books, etc.) and fill the empty spaces in your luggage with those, if you can and want.

Media and Internet: Check below for details, but in short: before you go, get a VPN (to access sites and services that are blocked for Cuba) and plan for mobile internet access: you can either get a local SIM card at the airport or use roaming from your phone operator (but triple check the rates and limits and keep an eye while you are there). Of course, download offline maps on Google Maps and any other apps and media you may want there, and pre-book (and pre-pay) any tours and experiences you can before traveling.

Advance Travel Information (D’VIAJEROS): Not sure if mandatory, but it’s easy: a day or two before the trip, go to the website, select your language and fill the information on what you are (not) bringing. You get a PDF with a QR code that you print or save to your phone, and show that when asked at the airport. Unlike Canada’s ArriveCAN, each passenger needs to fill their own form and get their own QR code.

Visa: Any visitor needs a visa (often referred to as a “tourist card”) to enter the country, but it’s inexpensive (around USD 20) and airlines often give you one as part of the ticket purchase; check with yours. Air Transat gave us the card inside the plane (hints: bring a pen and avoid mistakes; you can’t cross them and they will charge you for another form). Just fill (twice) your name, passport number and date of birth, show it on your way in, don’t lose it, return it on your way out and you are good.

Non-Americans / Non-Canadians: If you are not Canadian or American, and plan to visit the United States in the future, keep in mind that, as of January 2024, visiting Cuba prevents you from using the ESTA (“electronic visa”) program and you will need to apply for a regular US visa; so you may want to get your ESTA before visiting Cuba (or plan to get a US visa instead). This was a farewell gift from Trump that hopefully will change in the future, but keep it in mind for now.

Here comes the sun

Our arrival and return flights were in Varadero (VAR), which is a very popular destination for Canadians - quite a few get all-inclusive resorts and stay inside them for the entirety of their trips. That wasn’t really our thing - sure, we wanted a break from the Canadian winter, but we also wanted to see the country and talk to the locals, so we split our time between Varadero itself (for the beaches), Havana (the urbanized capital) and Boca de Camarioca (a smaller village closer to the Varadero airport).

The beaches in Varadero are magnificent and the water was warm and clear. We were lucky to have great weather during our stay - in fact, winter brings the sun down to levels that my caucasian skin can withstand. You can rent chairs for the day and/or drink coconut water for a few dollars, get lunch at a nearby restaurant or have it brought to you. If you want to just relax and enjoy the sun, that’s where you should go.

Getting around

The airport in Varadero was functional, albeit minimalistic - they used inexpensive webcams to take our pictures and we even to lend one of the officers a pen. Customs asks few questions (fewer if you are Canadian), but we were randomly stopped after getting our luggage. We were asked about our itinerary (it helped to have all the dates and addresses) and, after acknowledging how cannabis is legal in Canada and stating it was “not a judgement question”, they asked whether we ever had it; we said no, and that was everything.

Speaking Spanish (or, in our case, Portuñol) was quite helpful, but you can get around with English and some effort. We had a great recommendation for a taxi driver, with whom we pre-arranged pickup and drop-off at the airport and the transportation between our destinations according to distances. Going from Varadero to Havana and back typically costs around USD 100 for each trip (the price is for the car, regardless of the number of persons, but always ask). Getting from/to the airport will hover around USD 30.

Cuba is famous for the old-style cars used for tourists (other than those, most of what we saw were really old ones, nearly falling apart and the occasional luxury one, heavily contrasting with everything around it). The old-style cars do tours (a popular one being to visit Havana from Varadero and vice-versa). There are also horse-drawn carriages, pedal-powered taxis and buses, but we had no problems just using the taxis for long distance and walking everywhere else.

An interesting fact: the first letter in the license plate identifies the car’s assigned usage. Sources differ on the meaning, but a few that seem to be consistent are:

| First Letter | Meaning / Usage |

|---|---|

| A/B | Government-assigned (by Transportation Ministry) |

| C/D/E | Diplomatic (Consular / Diplomatic / Embassy?) |

| F | Revolutionary Army Forces |

| K | Temporary residents / foreign companies doing government business (later with “Cuba” written on a blue banner) |

| M | Ministry of the Interior |

| P | Private |

| S/W/Z | Religious institutions, cooperatives (Z/S = bikes, W = others) |

| T | Tourism |

Social perspectives

Even during our beach time, we walked around and talked to the locals (as we started giving some of the things we brought as gifts). At first, most people would tell how they were happy with the government and how things were good, but as we got closer to the less tourist-y places, we started to hear (and witness) a different story.

Outside of Cuba, people tend to align their opinions on the country with their left/right political leanings. For example, when Bolsonaro was Brazil’s president, his supporters will often tell you to “go to Cuba” when they run out of arguments (or even unprovoked just if you happen to not idolize him), while left-wing people will often overly praise the country’s performance on safety, education and healthcare, turning a blind eye to the human rights violations, lack of basic freedoms and the biased origins of those performance metrics.

This is a very complex subject, and I don’t expect to cover it in a single blog post from a week-long visit, but I would like to share some of the tidbits we learned from talking to the locals, from the guided tours (led by a sociologist and a geographer) and from consuming their local media and online content.

We highly recommend the tours above - as much as they have their personal opinions, they brought us lots of perspective on the country’s history (in particular, they helped us understand the extent of US assets that were seized, which explains why private lobby will never allow the US government to relent until those parties are compensated and why the local government has no hopes of negotiating a compensation, as neither the assets, nor wealth created by them are available) and the current situation, including the 2021 protests.

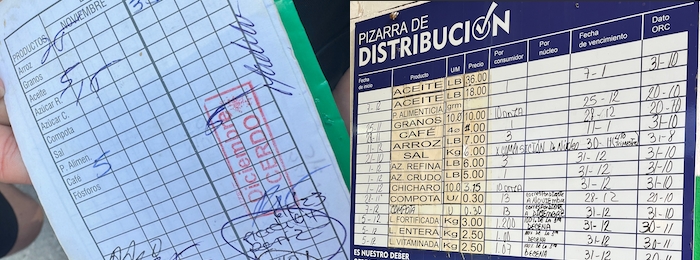

The thing that mostly stands out are the shortages. Food, medicine, toiletries, electronics, you name it: everything is in short supply and rationed. The bodegas - government-sanctioned stores for the locals - will check their libreta (ration book) and only sell the amounts they’re allowed to buy (when they have supplies).

We witnessed a semi-scheduled evening blackout of city lights around the public squares; locals are so used to it that our guide didn’t realize at first how scared we were. Sure, it is deemed safe to walk around at night, but it must be hard to go without electricity for hours when it hits residences (and it does).

As much as salaries are nearly the same for everyone, those with access to foreign currency (from working with tourism, for example) or resources (from relatives abroad) have a visibly different standard of living. They can buy things at the markets that are not available to the general population (at much higher prices), but they need to first get the foreign currency through a local bank card.

We noticed that that all the things we brought as regalitos (“gifts”, but they were actually donations) were gladly accepted, even by people that would obviously not use them - because they could be traded in alternative markets for the things they need and cannot get at the government stores. These trades are organized in the community by word of mouth, but also in WhatsApp groups. Checking that activity was an eye-opening experience.

As for the causes: the embargo (and US in general) definitely plays a role on that. Even those who blame the government admit things were better in the Obama years and are very afraid of a second Trump term. But the locals are quick to point out how many of the shortages can’t be explained by the embargo, as there are many things that are produced in Cuba and should be available in sufficient quantities.

Those conversations happened in hush-hush tone, as the government doesn’t take criticism as well as it says it does, and the electoral process is quite convoluted; in the higher instances, anything but sanctioning the central administration decisions is said to be not tolerated. Locals are proud of their country, but aware that they can’t speak freely about it, and that they aren’t compensated by social welfare as some external supporters would like to believe.

We learned is that doctors that work abroad (e.g.: in Brazil, where remote communities had significant social improvements thanks to them, until the right-wing government dismantled the program with offering no replacement) are paid a fraction of what the host country pays for their services, and the rest goes to the government. This sounds absurd in a capitalist logic, but might be be understandable if the government used that money to improve the lives of the locals (and maybe justify Cuba’s reputation for education, safety and health systems).

We wanted to check that in loco, but between the school break and our unwillingness to disturb hospitals in any way, we had to rely on the locals. They recognized and were proud of those achievements, but pointed out (and showed a bit) how the lack of investment in people and supplies degraded service in schools and hospitals in recent years. As for safety, crime is indeed low with nearly no weapons around, but locals are very afraid of the police (even more so with so many people are still incarcerated or disappeared after the 2021 protests).

Of course, these are random impressions I picked up; if you want some hard data with proper methodologies, I invite you to check the reports (in English) from the Observatorio de Derechos Sociales - the Spanish version was highly recommended by academics to whom we spoke. The report is quite critical of the government, but also very transparent about the methodologies and data sources, so you can make your own conclusions.

Media and the internet

As Portuguese native speakers, we were able to communicate with locals and and consume the local media. Television included some Latin American channels (seemingly unsupervised, but we were not sure how accessible they were to non-tourists). Government-ran Cubavisión seemed available everywhere, and Segundo Sol, a 2018 Brazilian soap opera dubbed in Spanish as “Nuevo Sol”, is popular among locals.

Local shows were, as expected, heavily loaded with unapologetic government propaganda - a youth-oriented show that presented itself as an educational block against media manipulation was basically accusing international media of doing that, while presenting the government’s point of view as the only unbiased truth.

The official newspaper is a daily set of around 8 pages that costs 20 CUP and limits to reporting policy changes and occasional cultural articles. There are some libraries and pop-up bookstores (the later mostly for tourists), but the selection is very limited.

Internet access is available, mostly through smartphones. Locals complain about the speed more often than they complain about price (but that was among those that actually had a smartphone). Some websites are indeed blocked by the government, but from our point of view, most of the blockings were done on the US sites/services side, which either block you, or don’t allow you to create accounts or handle payments from Cuba. A VPN works around that (and I recommend getting one before you go, for the reasons stated).

To get internet as a foreigner, you can either by an ETECSA SIM (or e-SIM) right at the airport, or get roaming from your phone operator. I usually avoid the later option, as it’s quite easy to rack up a huge bill, but my provider (Freedom Mobile) has a CAD$ 30 package that gives you 5GB for 90 days on a large list of countries that includes Cuba. I kept an eye to make sure I’d not go over it and it worked fine, while my wife went with the e-SIM, so we had a failover in case one of them didn’t work.

One unexpected bug/feature: while her e-SIM got under all the restrictions while outside of a VPN, mine didn’t. I got a British Columbia IP address (despite living in Ontario) and was able to access all the sites and services that were blocked for her. Of course I didn’t abuse that, but it was quite helpful as we were able to book a couple of tours that were only available online.

When visiting the library, I found a book that explains how the internet (and computers in general) work in Cuba, which (as a retrocomputing and computer history nerd lucky enough to read Spanish) I found quite interesting. It’s very deferential to the government mantras (even in contradictory points such as being proud of their pioneirism on mainframe capabilities yet noticing they were kickstarted by nationalized IBM assets), but it’s interesting to see how Cubans managed to get their online infrastructure working in such a challenging environment.

Is it worth to visit Cuba?

Definitely yes! It is a great place to get a breather from the Canadian winter, with friendly people and relatively affordable accommodations, but you should be aware of the situation and be prepared to see a lot of poverty and people struggling to get by. If you’re not comfortable with that, you should probably stick to the all-inclusive resorts.

On the other hand, if you want to check for yourself, get an unbiased perspective and/or help the locals, by all means spend some time out of the resorts, and get to know the real Cuba. You will be able to see the beautiful landmarks and the old cars, but also the real people and their struggles.

Most important: free your mind both from the demonizing and the idolizing of the country, the government system and the people running it, and try to understand the situation from the locals’ perspective. You won’t regret it.