A Hack is Born

You never know what you’ll find at Active Surplus - a must-go Mecca for electronics enthusiasts in Toronto (pics). Last week, I stumbled upon a box full of PC gamepads - at $2.50 each!

They used an old connector (see below) that would require an USB adapter, but I had a better idea: connecting them to a Raspberry Pi. Bought one (discounted to $2) and hacking ensued.

IBM-PC Joysticks

The IBM-PC used analog joysticks. But unlike analog sticks found in modern console gamepads, most PC controllers sucked. Almost none centered consistently, most required calibration, and several games didn’t support them, or ignored the analog aspect.

Fortunately, the $2 gamepad I purchased was digital - but used the PC DB15 Game Port connector, simulating an analog controller by outputting a mid-range value when no direction is pressed on the D-pad, and an extreme value otherwise.

My first impulse was to build an A/D interface, but I also wanted to map the “Turbo” (rapid fire) buttons as regular ones - and, of course, hack a bit. So I put my $2 investment on the line, by opening the controller and replacing its electronics.

Multiplexing

First problem: to use all the features I wanted, I’d need a lot of wires:

- 4 to read the directional pad;

- 6 for the standard buttons (4 front, 2 shoulder);

- 2 for the Turbo A/Turbo B buttons

- 2 for power (3.3V and GND).

Even if I just focused on the standard buttons and just used a single power line (connecting each button’s wire to the power when it is pressed and leaving it disconnected disconnected otherwise), that would still need 11 wires.

The original controller’s 10 wires worked because the “analog” D-pad only required one wire for each axis, and Turbo buttons (implemented with a 555 oscilator that changed the state of the A/B buttons when the TA/TB were pressed) didn’t have to be connected to the PC.

To solve that, I used a multiplexer chip. Those have a bunch of data inputs and (typically) one output, plus some data select pins. An external device (in our case, the Raspberry Pi) can set those pins to say “hey, give me the n-th input”, and the output will match the state (high or low) of that specific input.

Ideally, I’d use a 16:1 multiplexer (you feed 4 bits to select an input from 0 to 15, and it returns the output) like the 74151A. But I could not find one either at Active Surplus or Home Hardware (another cool place in Toronto to buy electronics parts), so I’ve settled for two 74151s (8:1 multiplexers).

I could have added a third chip (or transistor pair) to convert the 8:1s into one 16:1, but the multiplexing saved me so many wires that I could simply have two outputs, using the same 3 wires for data select on both chips, and letting the software decide which output it will check to find if a given button/D-pad direction is pressed.

With that setup, I just need 7 wires:

- 3 for data select;

- 2 outputs (the state from the selected pair of switches);

- 2 for power (3.3V and GND).

Pull-Up

Unfortunately, I couldn’t simply connect the switches to the multiplexer and be done with it.

As a software guy, I always thought of digital electronics in terms of true/false, or 0/1. However, a given point on a digital circuit can have three possible states:

- Connected to the “+” level of the power source;

- Connected to the “-“ (GND) of the power source;

- Not connected to anything.

This brings a problem: a switch (like the ones on the controller) produces either a connection (which will be one of the two first states) or the lack of one (the third state), but most digital electronics (including the multiplexers I’d use and, in most cases, the Raspberry Pi itself) expect “+” or “-“ (usually referred to as “high level” and “low level”).

It is a very common design issue, but it has an equally common solution: first, you connect one of the switch terminals to the level you want to map to “pressed” (here, low level), and the other terminal to the circuit that will check for high or low, just like a light switch.

Here comes the trick: also connect the opposite level (high, in our case) to the output, along with the terminal. When the button is released, the last conneciton sets the high level. But it creates a problem: when you press the button, high will connect to low - and you should never cross the streams.

To avoid that situation (a short-circuit), add a resistor to this last connection. It will turn the short-circuit into just a small power consumption, also making the low level “win” when the button is pressed (image cc-by C4VC3):

Such a resistor is called a “pull-up” because it “pulls” the otherwise disconnected state into the high level (would be a “pull-down” if we wired the other way around, with open switch = low).

Protecting the Pi

So I’d need a pull-up resistor on each button/D-pad direction. But there was one last thing: the Raspberry Pi GPIO connector doesn’t have this name (General Purpose Input/Output) in vain: any pin (that is not a fixed +5V/+3.3V/GND, check the diagram) can be configured to be either an input or output. In our case, we’ll configure three to be outputs (our multiplexers’ data selector pins) and two to be inputs (the result from each multiplexer).

Problem is: what if the programmer does a mistake? Specifically, what if an input pin is set up as output? Well, as soon as the incoming level becomes different from the level we output (a button press or release), it will short-circuit the Pi. We can easily prevent that by adding a protection resistor to each output, preventing a short if the software goofs up.

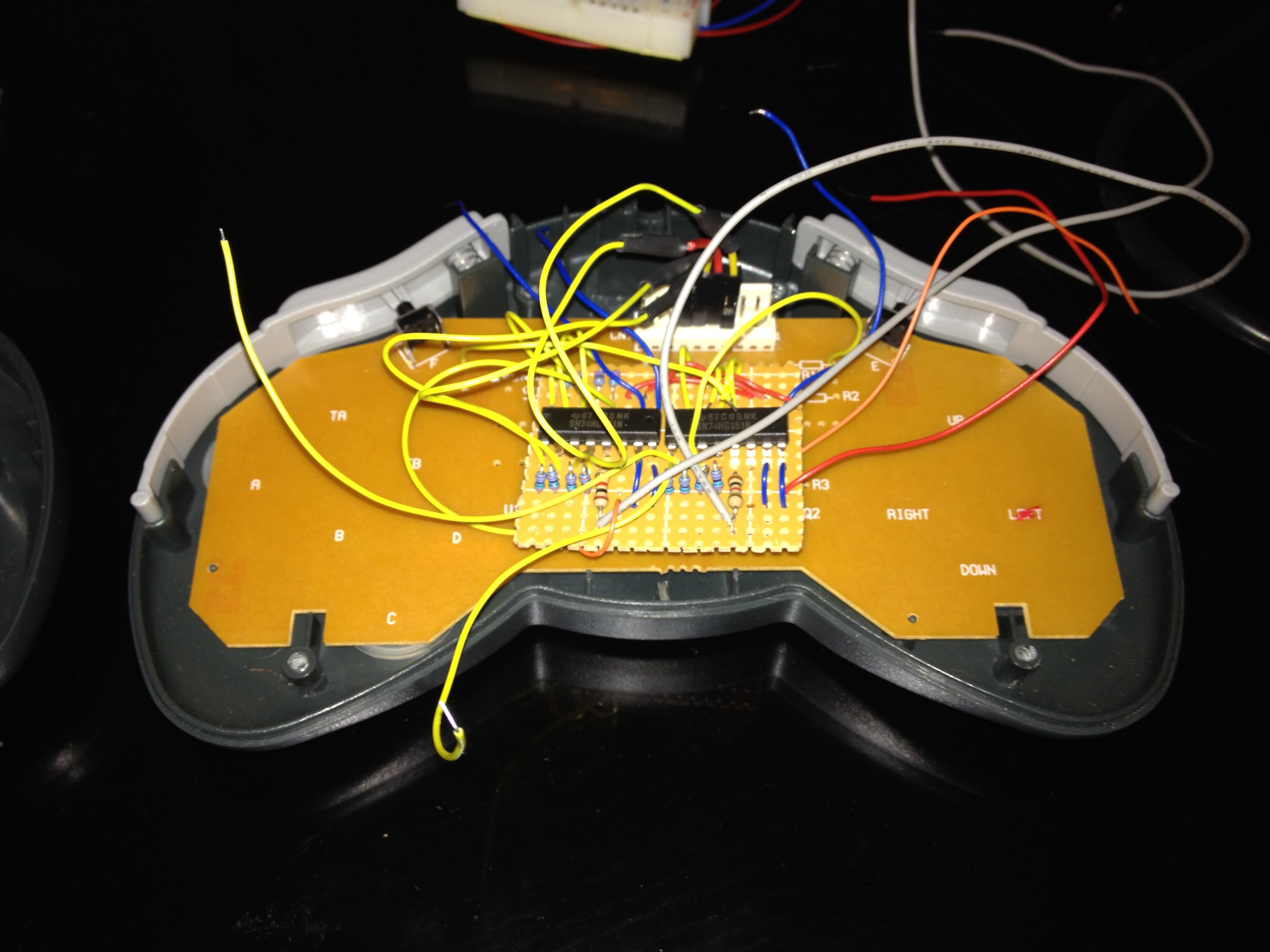

Each multiplexer input has a pull-up resistor connecting the high level to its switch (yellow wires). Unused inputs are connected to high level by yellow jumper wires, because some chips dislike non-connected inputs, even if unused. Data selectors (blue wires, right) for each chip are linked by the red jumper wires, and each output (gray wires, left) has a protector resistor.

Resistor values

The resistance (in ohms, or Ω) values for resistors used for pull-up and protection can be calculated, but typical values are widely known and used. I went with 1KΩ for the protection and 15KΩ for the pull-ups (would go with the usual 10KΩ, but the others were close at hand).

Building

I decided to use a breadboard, that is, a circuit board with series of short connections in which you can lay out components and complement the connections with wires. Not the best choice for such a project (see below), but it worked.

Initial testing of the circuit was performed by using another breadboard (a solder-less one), in which I connected the outputs to a couple of LEDs and tested different combinations of the data selector and inputs to see which would turn the LEDs off.

Integrating

After I had a working board, I had to make it work with the joystick. I removed all components from the joystick’s original print circuit board (which were responsible for translating the D-pad into the simulated analog signal and performing the Turbo). Then I found convenient spots to connect the GND signal and the inputs so they’d be grounded (logic low) whenever one distinct direction or button was pressed.

I wasn’t able to use the Turbo buttons as planned: each of them had a terminal connected to an end of the matching button (A or B) and the other end was tied together, with no connection in-between. I’d likely need to perforate the board to create new connections (and re-route existing ones). Possible, but too much work - and I just wanted to see the hack working.

The joystick cable had an 10-pin header that plugged into the board, which I had to disconnect: the buttons connected to it should now go to the multiplexers. Also, I wouldn’t need the DB15 end, so I reversed the cable: plugged the 10-pin header into the RPi’s GPIO, cut the DB-15 and connected its wires to my circuit.

The header fit the “odd” GPIO row nicely:

- Pin 1: +3.3V;

- Pins 3, 5, 7: data selection (output from Pi);

- Pin 9: GND

- Pins 11 and 13: button/D-pad state (input to Pi);

Testing

All done - let’s test it. On the Raspberry Pi, I installed Python and the GPIO Python libraries:

sudo apt-get install python-dev python-rpi.gpio

We’ll run the Python interpreter as a superuser (to ensure it has low-level I/O access):

sudo python

Pins 1 and 9 are fixed (+3.3V and GND), but the others must be configured in the same way they were wired on the controller:

import RPi.GPIO as GPIO # We'll use this library

GPIO.setmode(GPIO.BOARD) # Use the (sane) pin numbers

GPIO.setup(3, GPIO.OUT) # Data select pins

GPIO.setup(5, GPIO.OUT)

GPIO.setup(7, GPIO.OUT)

GPIO.setup(11, GPIO.IN) # Input from first multiplexer

GPIO.setup(13, GPIO.IN) # Input from second multiplexer

Finally, a simple code snippet that tests the D-pad. It will continuously print the direction being pressed (both of them if it is a diagonal):

GPIO.output(5, True) # The four D-pad inputs map to pin 5 = high

while True:

print

for a in [True, False]: # Test all combinations for pins 3 and 7

for b in [True, False]:

GPIO.output(3, a)

GPIO.output(7, b)

if (GPIO.input(13)==0): # Did we press this combination button?

if (not a and not b): # Yes, print the D-pad direction mapped to it

print "RIGHT",

if (not a and b):

print "LEFT",

if ( a and not b):

print " UP",

if ( a and b):

print "DOWN",

See it in action:

It can be expanded to test the buttons, just by configuring the correct data selection on the pins 3, 5 and 7, and checking the appropriate input pin (11 or 13).

Conclusions

My next step would be adapting an existing joystick driver to my setup. But upon testing, I found the gamepad a bit… cheap. The D-pad registers diagonals most of the time (you have to press right in the middle to avoid it).

It made me realize I fulfilled my learning goals (knew almost nothing about GPIO programming, multiplexers, pull-ups, etc., before this project; corrections are welcome), so I’ll keep it as-is and move on.

Another lesson learned: a breadobard is a bad approach for such a project. It takes more space than it should, wires gets clumsy and easily snap out of place, and soldering becomes hard (and crappy) because components are squeezed to fit the breadboard layout. One of these days I’ll learn how to make printed circuit boards.

Anyway, it was a great warm-up for my next big project: using the PiScreen to build a version of the RPi Game Boy. I’ll also tinker with that one (want to include all SNES gamepad buttons). Will be my first project involivng 3D printing, and I’m excited!

Comments

Naner Nunes

Incrível Chester. Parabéns pela qualidade do artigo, esses são os tipos de coisas que também gosto de fazer. Virei seu fã desde a pelestra na RubyConf sobre o emulador de Atari 2600 com Ruby. Parabéns e seguindo.

chesterbr

Heh, obrigado! Eu ainda tenho que voltar pro ruby2600 para tentar otimizar um pouco, mas por ora estou focando em destruir coisas com o ferro de solda :-D

Abraço!

Payam Rastogi

I am trying to build a robot using raspberry pi somewhat similar to line follower. I was wondering if it is possible to connect ns joy con to raspberry pi and use them to send signal to robot. I searched a lot and found pybluez might be helpful. But not sure how to use it to read signal from joy con connected to raspberry pi using bluetooth. Any advice.

chesterbr

Sorry for the delay. I would suppose it is possible, for here is a video of someone configuring the RetroPie emulator to a JoyCon: https://www.youtube.com/wat... . I have no experience with pybluez, but I'd first try some packed software like that (to confirm the RPi, controller and Bluetooth gear are compatible), then fiddle with pybluez. Good luck!